British Losses in the Falklands (1982)

|

| The County-class destroyer HMS Glamorgan, which holds the dubious distinction of being the first and last ship to be damaged in the Falklands War |

The Falklands War is the only large-scale post-WWII naval campaign. So even though the technologies and tactics used are now somewhat dated, it remains one of the best resources for understanding modern naval warfare.

During the conflict, the British lost 6 ships and had another 16 damaged (I will be using the British records for this post rather than the significantly higher Argentinian claims - this is not because the British are inherently more trustworthy, but because in every war the attacker's claims are always less accurate than the defender's). This post will aim to provide an overview of where these ships were and what they were doing when they were attacked to see if there are any patterns that can inform our understanding of naval warfare.

The Opening Actions

The Falklands War began on 2 April 1982, with the Argentinian invasion of the islands. As with nearly every war, this was not a "bolt from blue" and was proceeded by a lengthy period of increasing tensions that culminated in the 19 March events on the island of South Georgia. This meant that the British already had limited assets in theater and were able to react quickly. However, assembling the necessary forces still took time and the main fleet did not reach the area until late April.After the initial British operations against South Georgia, which were outside the range of the Argentinian fighters, British attention turned to establishing air supremacy. This consisted of a three-pronged attack on 1 May against Argentinian airfields on the Falklands by RAF bombers (the famous Black Buck raid), carrier-based Harriers, and naval gunfire.

Three ships were involved in the gunfire mission. The County-class missile destroyer HMS Glamorgan (2x 4.5" guns, Sea Slug, and Sea Cat) and the Type 21 frigates HMS Arrow and HMS Alacrity (1x 4.5" gun and Sea Cat). The air defense systems on all of these ships were thoroughly obsolete and the failure to assign a single ship with modern air defenses for an attack on an airfield is somewhat inexplicable. Perhaps the British were either more concerned about defending their main fleet, or did not wish to risk their limited number of modern air warfare ships (and their best short range weapon, Sea Wolf, was only mounted on ships that lacked a deck gun).

Predictably, the Argentinians responded with a large strike launched from the mainland. However, only a small number of Dagger fighters (an Israeli version of the French Mirage V) managed to locate the British ships (this would be a theme throughout the war and serves to demonstrate the inherent survivability of ships). Against this attack the British were virtually defenseless and all three were damaged by bombs and cannon fire, but armed only with iron bombs, the Argentinian pilots failed to score any direct hits. If they had been a little luckier, this opening engagement could have been a disaster for the British.

The next incident was the famous 4 May Exocet attack that resulted in the loss of the Type 42 destroyer HMS Sheffield. This was again the result of a rather poor choice by the British, as when she was hit, Sheffield was operating independently as part of a radar picket line (necessitated by the British lack of carrier-based airborne early warning). While a radar picket line was a good idea, the decision to use the best British air defense ships for it was questionable. Any reading of WWII history should have shown that picket ships were extremely vulnerable. Further, while the Sea Dart missile was extremely valuable as part of a layered defense, it was marginal against low altitude targets.

|

| HMS Sheffield burning after being hit by two Exocet missiles |

However, the British were learning from these mistakes and began deploying pairs of Type 42 destroyers (Sea Dart) and Type 22 frigates (Sea Wolf) to create overlapping high and low altitude coverage. On 12 May, one of these pairs consisting of HMS Glasgow and HMS Brilliant came under attack from eight Argentinian Skyhawks while conducting another bombardment of the Port Stanley area. The Sea Dart system on Glasgow failed early, but the Sea Wolf system on Brilliant shot down three Skyhawks before it too failed (this appears to have been a software glitch that caused the still somewhat experimental system to fail to recognize the second flight of Skyhawks as valid targets) . The remaining Skyhawks then scored a direct hit on Glasgow, and while the bomb overpenetrated without exploding, it did damage the destroyer's engines and forced her to leave the theater for repairs.

The Main Attacks

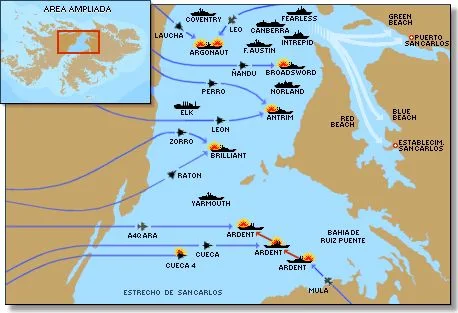

21 May brought the main amphibious landing (codenamed Operation Sutton) and marked the single largest naval engagement of the war. The British attack began shortly after midnight with the first waves ashore well before dawn. But after the element of surprise was gone and the ships were pinned to a fixed location, the Argentinians attacked in force with Daggers and Skyhawks. Logically, the British naval forces were arrayed with the escorts between the air threat and the transports. This resulted in the warships absorbing the bulk of the attack while the vulnerable transports survived unharmed. |

| A map of the 21 May action, taken from the excellent HMSBrilliant.com |

Before the main force of Argentinian jets arrived from the mainland, some light aircraft based in the Falklands attacked. However, only a single MB.339 armed with rockets and cannon managed to inflict minor damage on the Leander-class frigate HMS Argonaut.

When the heavier planes reached the area, the County-class destroyer HMS Antrim was the first victim. Her obsolete Sea Slug battery unsurprisingly failed to ward off the attack and she was hit by a 1000 pound bomb that failed to explode. The Type 22 frigate HMS Broadsword shot down one Skyhawk (this kill was also claimed by two other ships), but then her Sea Wolf system failed and she was hit by cannon fire and a bomb near miss. Next up was HMS Argonaut again. The two bombs that hit her failed to explode, but still inflicted enough damage on the small ship to send her home. The Type 22 frigate HMS Brilliant was also lightly damaged by cannon fire.

One thing that should be kept in mind while reading this short account of the action is just how much it leaves out. There were dozens of bombs dropped that missed their targets, all of the ships involved were firing missiles, machine guns, and chaff, and the Harrier force shot down no fewer than nine Argentinian planes. Altogether, there was considerable confusion on both sides, which more than explains the relatively poor results.

There was no confusion to the Type 21 frigate HMS Ardent, which had been dispatched several miles south of the landings for a bombardment mission. Armed only with Sea Cat and lacking the mutual support of the larger force, she came under heavy attack from multiple waves of Argentinian planes. By the end of the day Ardent had sustained numerous bomb hits, leaving her listing and on fire as the crew abandoned ship.

|

| HMS Ardent after she was attacked |

The next day marked a pause in the fighting as bad weather over the mainland prevented Argentinian flights. But on 23 May the invasion force again came under attack, albeit on a smaller scale than 21 May. This time the primary target was the Type 21 frigate HMS Antelope, which was screening the landing. Although her Sea Cat system may have downed one of the Argentinian Skyhawks (this kill was more likely by a Sea Wolf from HMS Broadsword or a land-based Rapier missile), it was not enough to save the ship and she was hit by a pair of 1000 pound bombs. Both failed to explode on contact, but one detonated later that day when the British were attempting to remove it. This explosion started fires which ignited the magazines, ultimately leading to Antelope sinking the following day.

|

| HMS Antelope after burning all night, soon afterwards she broke in half and sank |

For 24 May the Argentinians changed their tactics, pushing deeper into the bay and targeting transports rather than warships. This is remarkably successful and the Skyhawks score bomb hits on three of the British Round Table-class landing ships: RFA Sir Galahad, RFA Sir Lancelot, and RFA Sir Bedivere. While these hits start fires on Sir Galahad and Sir Lancelot, none of the bombs exploded. One Skyhawk is shot down by surface fire, but it is again unclear who scored the kill.

Although this attack did not inflict serious damage, it reveals a fundamental weakness of the British deployment - its lack of area air defense. The destroyers and frigates (especially the modern Type 22 with Sea Wolf) assigned to defend the landings were reasonably capable of self-defense, they were largely incapable of defending other ships. The only ships that could do so were the Type 42 destroyers, which were mostly kept back to defend the carriers. If the Argentinians had focused on attacking the transports from the beginning, it could well have crippled the landings while the British escorts off San Carlos would have been little more than bystanders.

Changing Tactics

The British seem to have realized this weakness and on 25 May became more aggressive in their deployment. Instead of remaining just off the landing beaches, they stationed the Type 42 destroyer HMS Coventry, accompanied by the Type 22 frigate HMS Broadsword, well to the north near Pebble Island. Initially, this worked well, with Coventry claiming two kills. Another Skyhawk that slipped past and made it to the landing area was also shot down, possibly by a Sea Cat from the Leander-class frigate HMS Yarmouth.However, the Argentinians quickly realized what was happening and sent a strike to attack the picket ships. As the Skyhawks approached at low altitude to avoid Sea Dart, the Sea Wolf system on Broadsword malfunctioned and both ships were hit. Broadsword suffered only minor damage from a bomb that failed to explode, but Coventry was hit by three bombs (two of which exploded) and capsized in a matter of minutes.

|

| HMS Coventry listing as her crew abandons ship |

Coventry was not the only ship sunk on 25 May. That evening the Argentinians used their Exocet-armed Super Etendards to attack the British carriers, which were still stationed far to the east of the Falklands. The British successfully detected the attack and deployed chaff and decoys to confuse the incoming weapons. However, one ship was not fitted with these system - the civilian aviation transport Atlantic Conveyor. Even worse, she was just outside of the range of the Sea Wolf missiles on the nearby HMS Brilliant, which was escorting the carrier HMS Hermes. Both Exocets hit this large and vulnerable target, leading to uncontrollable fires and forcing her crew to abandon ship.

|

| Atlantic Conveyor the day after the attack, a burned out wreck she would remain afloat until the 28th |

After the damaging attacks of 25 May, the weather again turned bad with heavy low clouds that hindered Argentinian air operations. These conditions persisted for the next two weeks, giving the British a much-needed respite. Although limited air raids continued and a handful of Argentinian jets were shot down (three by the Type 42 destroyer HMS Exeter), the only damage the British naval forces suffered during this period was the bombing of the civilian tanker British Wey north of South Georgia. This attack was conducted by an Argentinian C-130 cargo plane and the bomb inflicted only minor damage.

In a separate attack on 8 June, the Type 12M frigate HMS Plymouth came under attack from five Daggers while returning from a bombardment mission in the Falkland Sound. Armed only with the obsolete Sea Cat, she was nearly as defenseless as the LSL's and was hit by no fewer than four bombs, all of which failed to explode. Amazingly, Plymouth was back on the gunline before the end of the war.

Ironically, the first British ship to be damaged during the conflict was also the last. On 12 June, HMS Glamorgan was again shelling Argentinian positions off Port Stanley, this time in preparation for the final British ground assault on the remaining Argentinian stronghold. However, the Argentinians had recently devised a ground-based Exocet launcher using missiles taken from one of their destroyers. Glamorgan detected the attack and the first missile missed, but the second one struck a glancing hit on the helo deck. With her hangar on fire, the stoutly-built County-class destroyer was still able to exit the area at high speed.

As can be readily seen from this breakdown, 17 (77%) of the ships lost or damaged were hit while conducting operations close to shore. More interestingly, only 1 of these 17 ships was actually hit by a shore-based weapon - the threat did not come from being close to land, but from spending time where they could be easily observed by the enemy. This is further confirmed by the fact that 3 more ships were lost or damaged while on air defense stations where they were forced to reveal their position. Only 2 (9%) of the ships were lost or damaged while operating freely at sea.

In short, an analysis of the British losses in the Falklands War strongly confirms the tenant of naval warfare that a ship's advantage is its mobility and ability to disappear into the sea. However, it also reveals some other lessons. First, ships must have mutual support - British vessels operating independently were far more likely to be sunk than those operating in large formations. Second, cheap ships cost more in the long run - if more ships had been equipped with Sea Wolf and Sea Dart instead of Sea Cat and Sea Slug, then British losses would have been far lower, and if the Type 42 destroyers had been given both systems instead of just the high altitude Sea Dart, then it is quite possible that both HMS Sheffield and HMS Coventry would have survived. Third, being afraid of risk can lead to higher losses - throughout the campaign, the British held their carriers and their best air defense ships far from the action when a more aggressive use of these assets could easily have turned the tables. And fourth, know yourself and know the enemy - the British often appear to have been figuring things out on the fly that they should have known before hand.

The Final Actions

On 8 June the situation changed. As their ground forces advanced east across the island, the British had begun shuttling reinforcements by sea. However, they entirely neglected to provide escorts for these transports and, as could be predicted, this eventually turned out very poorly. The victims were the LSL's RFA Sir Galahad and RFA Sir Tristram. After landing troops at Fitzroy, south of Port Stanley, on 7 June, they returned on 8 June with additional soldiers. This time they were unable to unload on schedule and the two transports spent most of the day anchored offshore until Argentinian Skyhawks arrived. Sir Tristram was hit by one bomb and Sir Galahad by two or three. Both ships were abandoned although Sir Tristram was later recovered and returned to service after the war. |

| RFA Sir Galahad on fire off Bluff Cove |

In a separate attack on 8 June, the Type 12M frigate HMS Plymouth came under attack from five Daggers while returning from a bombardment mission in the Falkland Sound. Armed only with the obsolete Sea Cat, she was nearly as defenseless as the LSL's and was hit by no fewer than four bombs, all of which failed to explode. Amazingly, Plymouth was back on the gunline before the end of the war.

Ironically, the first British ship to be damaged during the conflict was also the last. On 12 June, HMS Glamorgan was again shelling Argentinian positions off Port Stanley, this time in preparation for the final British ground assault on the remaining Argentinian stronghold. However, the Argentinians had recently devised a ground-based Exocet launcher using missiles taken from one of their destroyers. Glamorgan detected the attack and the first missile missed, but the second one struck a glancing hit on the helo deck. With her hangar on fire, the stoutly-built County-class destroyer was still able to exit the area at high speed.

Lessons Learned

On 14 June the Argentinian forces surrendered, bringing an end to the war. Of the 22 British ships lost or damaged in the fighting, 7 were hit while conducting shore bombardment, 5 while shielding the landing beaches, 5 while unloading equipment to the landing beaches, 2 while detached for offensive air defense, 1 while acting as a radar picket, 1 while sailing with the main fleet, and 1 while traveling on the high seas.As can be readily seen from this breakdown, 17 (77%) of the ships lost or damaged were hit while conducting operations close to shore. More interestingly, only 1 of these 17 ships was actually hit by a shore-based weapon - the threat did not come from being close to land, but from spending time where they could be easily observed by the enemy. This is further confirmed by the fact that 3 more ships were lost or damaged while on air defense stations where they were forced to reveal their position. Only 2 (9%) of the ships were lost or damaged while operating freely at sea.

In short, an analysis of the British losses in the Falklands War strongly confirms the tenant of naval warfare that a ship's advantage is its mobility and ability to disappear into the sea. However, it also reveals some other lessons. First, ships must have mutual support - British vessels operating independently were far more likely to be sunk than those operating in large formations. Second, cheap ships cost more in the long run - if more ships had been equipped with Sea Wolf and Sea Dart instead of Sea Cat and Sea Slug, then British losses would have been far lower, and if the Type 42 destroyers had been given both systems instead of just the high altitude Sea Dart, then it is quite possible that both HMS Sheffield and HMS Coventry would have survived. Third, being afraid of risk can lead to higher losses - throughout the campaign, the British held their carriers and their best air defense ships far from the action when a more aggressive use of these assets could easily have turned the tables. And fourth, know yourself and know the enemy - the British often appear to have been figuring things out on the fly that they should have known before hand.

Comments

Post a Comment